By Dionne Aminata

Before I joined the K–5 curriculum writing team at IM, I was a K–8 regional math content specialist for a public charter organization that largely consisted of Title I schools, or schools receiving federal funding to support a large concentration of students in poverty. Prior to that I had experienced the joys and challenges of serving communities like these as a teacher and math coach in South Central Los Angeles and Crown Heights Brooklyn.

Underlying these challenges are decades of achievement data that show a consistent gap between black and brown students and their white and Asian counterparts. A 2018 TNTP report, The Opportunity Myth, points to inequities in our education system that disproportionately affect black and brown students, including limited opportunities to engage in grade-level tasks. Like many educators who are passionate about this work, I made it a personal goal to seek out and reveal the brilliance of each student by, among other things, engaging all of them in culturally responsive and grade-appropriate instruction.

I recognize that working to mitigate systemic inequities in math education is a huge undertaking. For this reason, I was thrilled when I learned that IM has a targeted approach to support the needs of Title I schools. Title I schools largely serve black and brown students. A 2019 EdBuild report, $23 Billion, details that despite laws and decades of efforts, more than half of schools in the US are racially segregated, with 26% of students in white districts and 27% in non-white districts. Although there are students in high-poverty districts across all racial groups, 5% of students are in high-poverty white districts, while 20% of students are in high-poverty non-white districts. At IM, we understand that focusing our work on supporting Title I schools provides a unique opportunity to study the needs of schools serving predominantly black and brown students.

A question we often ask at IM is, “What can a curriculum do?” Our mission at IM is to create a world where all learners know, use, and enjoy mathematics—regardless of race, ethnicity, language, gender, ability, and socioeconomic background. This question about its potential also raises this follow-up question: “What are the limitations of a curriculum?” While we realize that the design of our curriculum does not guarantee success for all students, we have taken steps to intentionally highlight features of our curriculum design that support efforts to mitigate inequities in math education.

Below are two features.

As a writing team, we studied culturally responsive pedagogy. We learned that the lesson structure we use in all IM curricula, K-12, is already aligned to the lesson structure proposed in Zaretta Hammond’s book, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain (2015): ignite, chunk, chew, and review.

The warm-ups include instructional routines such as Estimation Exploration and Which One Doesn’t Belong which ignite students’ brains by allowing them to bring their prior knowledge and personal experiences to the lesson. Following the warm-up are 2–3 lesson activities that build upon one another and chunk the learning. Throughout each activity, students are sharing their thinking and developing their understanding of the content. The activity syntheses, allow students to chew, or reflect on and process the information in digestible chunks. After actively processing the learning both independently and collaboratively, the lesson synthesis and cool-down give students an opportunity to review and apply what they have learned in the lesson.

Another feature of culturally responsive pedagogy, however, was not readily present in our curriculum. In Geneva Gay’s book, Culturally Responsive Teaching (2018) she writes, “Much more cultural content is needed in all school curricula about all ethnic groups of color… to fill knowledge voids and correct existing distortions.” (pg. 192) Many of the problem-solving situations we had written were generic situations such as those involving animals, school supplies, racing, and commuting to school. We realized that in our efforts to write situations that would include all students, we were missing out on providing opportunities for students to learn about ethnically diverse cultures through a positive and mathematical lens.

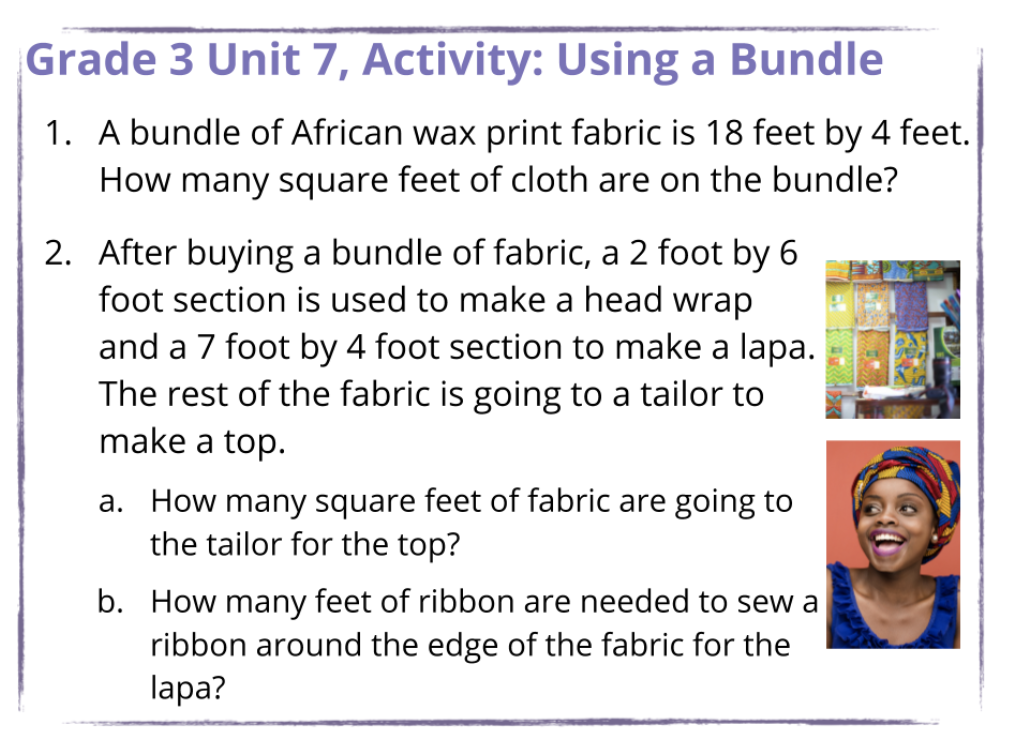

While discussing a unit on perimeter and area of rectangles with Zack Hill, lead writer for grade 3, we brainstormed ways to respond to Gay’s call to action. We centered a lesson on the purchase of a rectangular piece of African wax print fabric to make a head wrap and lapa (a wrap skirt). Students are asked to find the area and perimeter of the fabric.

Before digging into the problem, students warm-up with a Notice and Wonder routine to ignite student experiences with African fabric or fabric in general.

What do you notice? What do you wonder?

After the warm-up, students engage in an activity where they learn about the geometric patterns on African wax print designs, and use quadrilaterals to design their own wax print pattern. They then problem-solve to find area and perimeter in the second activity.

A significant amount of research was involved in creating this task, even though, as an avid student of West African dance, I have plenty of personal experience buying African wax print fabric to make lapas and head wraps. Not only did Zack and I learn a lot throughout the writing process, but we found comfort in knowing that students across the country would have a window into African culture, and experience it in a positive and mathematical way.

I think about how my former students in Brooklyn, NY would have engaged in a lesson like this. I had several African students in my classroom for whom lapas and head wraps were staple parts of their wardrobes at home or at special events. I also had students from India and the Middle East where colorful rectangular pieces of fabric were often purchased in the same way. For them, this lesson would be a reflection of their cultures, which would remove the barriers associated with making sense of problems where there is little or no contextual background. My former students and students like them might be empowered mathematically by a lesson like this, since they would be able to support the teacher during the launch of the activity and serve as a resource for students who are not familiar with the context. They would have an opportunity to access a grade-appropriate task that centers their experience and is designed for them to succeed.

Next Steps

How are you making sure that all learners have opportunities to engage in rigorous, culturally relevant, and grade-level content? Follow our blog to learn more about how IM’s K–5 curriculum is tackling this issue.