By Maureen D. O’Connell, IM K–5 Math™ Pilot Teacher,

IM Certified® Facilitator for IM K–5 Math

“The more intensely interested a teacher is in a student’s thinking, the more interested the student becomes in his or her own thinking.”

—Eleanor Duckworth

Whether we teach in-person or virtually, the goal of IM K–12 Math™ remains the same: to help students learn math by doing math.

IM’s problem-based lesson structure and inviting instructional routines elevate student thinking. When students say and show their math ideas, teachers better understand what they know or are able to do and can leverage moves to advance student thinking. IM supports distance teachers in receiving and acknowledging this thinking that students gift us as valuable. It positions all students as capable mathematicians doing grade-level work, and supports teachers as they create meaningful next steps.

Fellow IM Facilitator and Grade 8 Math Teacher Marcelle Good and I recently collaborated on a free IM Certified webinar to share strategies used for last year’s full remote and hybrid distance learning. We shared ideas that we and our colleagues used to adapt instructional routines, strengthen online classroom communities, and elicit student thinking. Most importantly, we wanted to value and celebrate this gift of student thinking in a virtual environment.

Thinking about equity, Marcelle and I acknowledged that many schools and students lack the material or people resources to use these tools as we did. We celebrate the efforts that all teachers made to reach their students in vastly different circumstances. This is what worked in our remote settings.

Discussion with colleagues and students consolidated central beliefs and teaching moves that facilitated positive, interactive math classes in distance learning.

- In order for students to freely share their rough draft and deep thinking, they must feel part of a safe mathematical community where all ideas are welcome.

- Teachers must be curious about and trust student thinking to drive learning. Student work should be the thread that connects and furthers the lesson learning goal.

- Students must have the opportunity to listen to, respond to, and value each other’s thinking. Synchronous time is best spent with students sharing and discussing each other’s work.

- Students learn by collaborating with each other. Time for working with peers allows for students to co-create understanding. We are better together.

Central Belief #1:

Cultivating a Mathematical Community

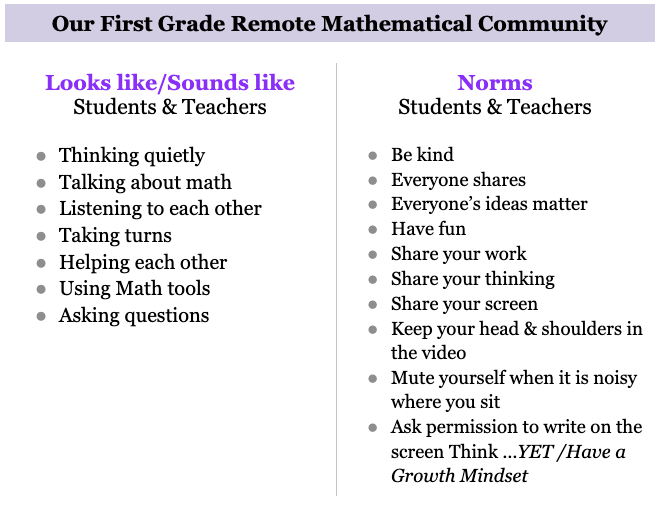

At every grade level, we agreed that in order for students to freely gift us with their work and thinking, time must be given to create a safe and welcoming mathematical community where all students’ ideas are celebrated. We created norms and noticed how the norms for these remote communities differed slightly from our in-person classes.

Here is an example from my grade 1 remote classroom:

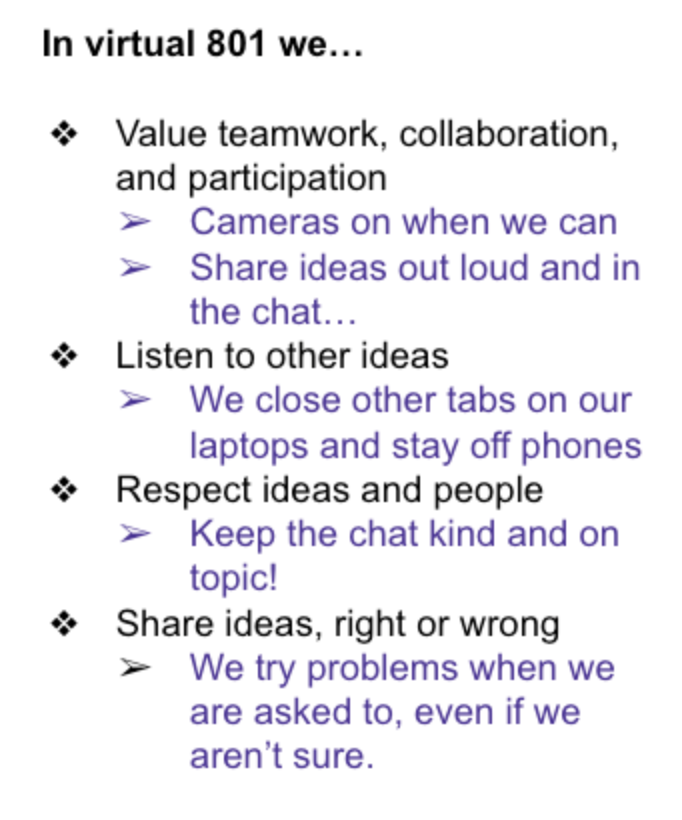

And here is an example from Marcelle’s Remote Grade 8 IM classroom…

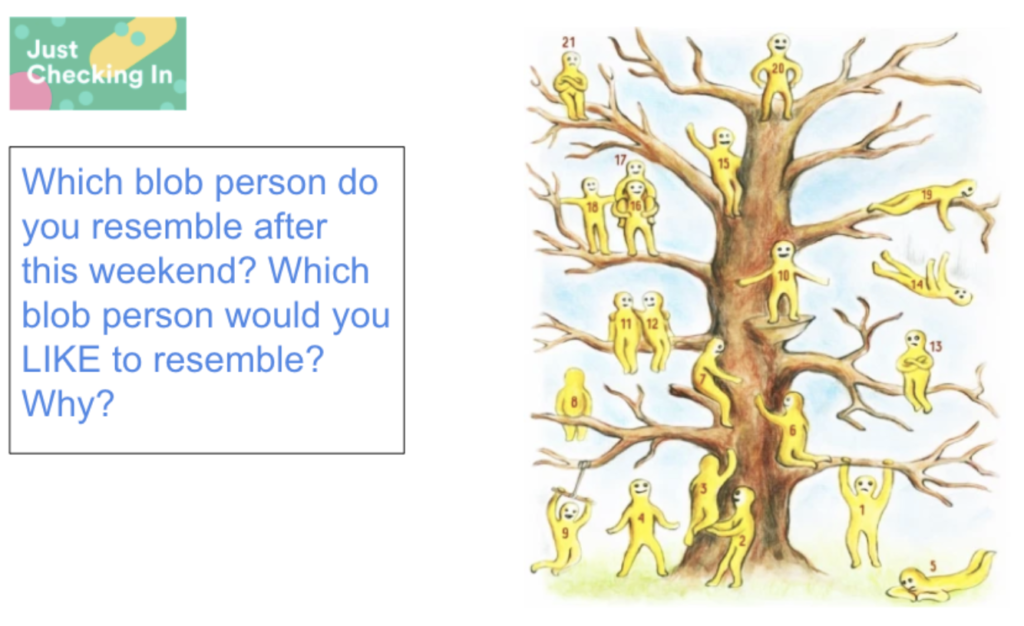

To foster a sense of community online, we used a variety of check-ins. K–5 students shared something important to them.

A grade 1 student-created check-in made on SeeSaw. On a scale of stuffie, how are you today? (Guest appearance from the IM Workbook in #4!)

Eighth graders loved seeing where they were on this blog person scale.

Central Belief #2:

Teachers are curious about and trust student thinking to drive learning.

Both the math content warm-ups and Math Language Routines give students opportunities to show what they know and are able to do in the moment. These routines position students for learning during the related lesson activities.

It then became critical that students have tools and strategies for sharing their thinking.

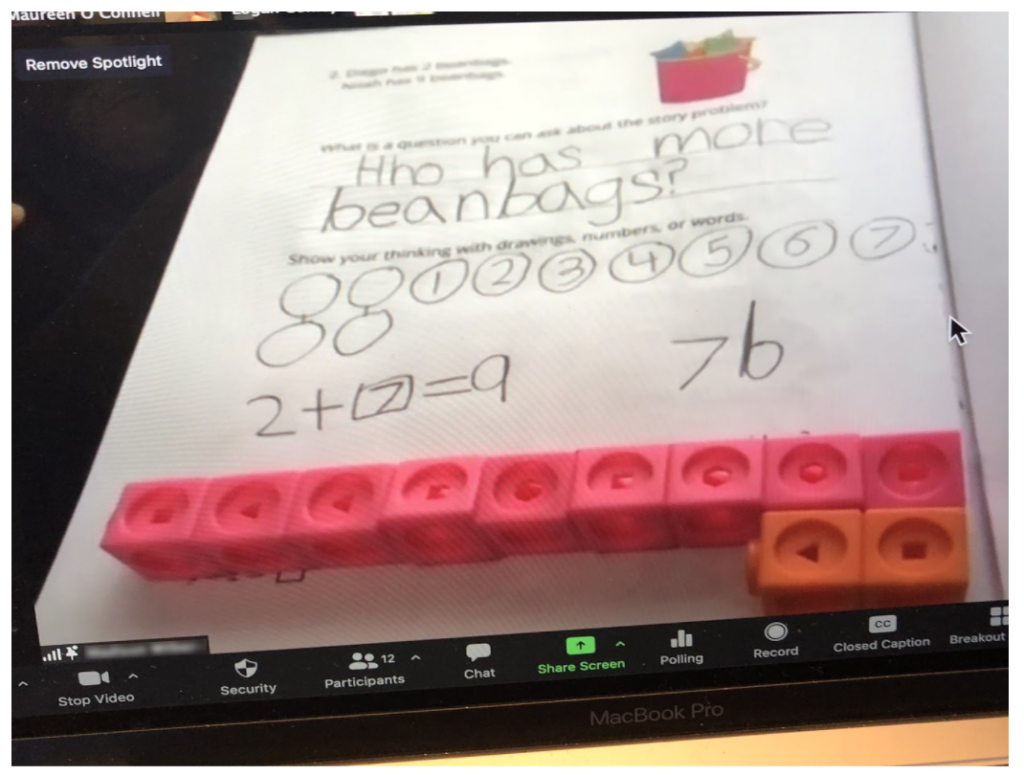

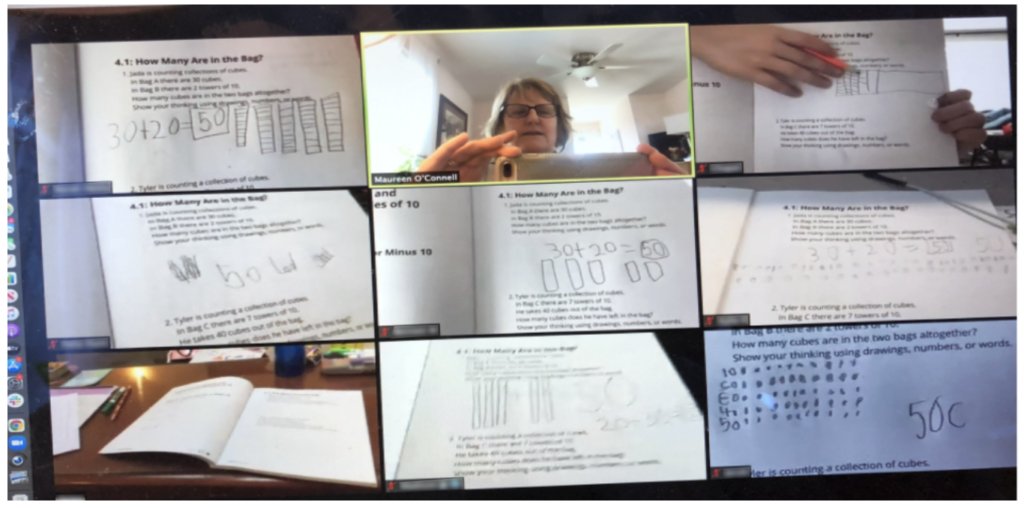

Strategy: Use student devices as document cameras, and use the meeting Spotlight for Everyone tool.

This student used their iPad to allow us to see their workbook page clearly. The teacher used the spotlight setting to allow all students to examine the work more closely.

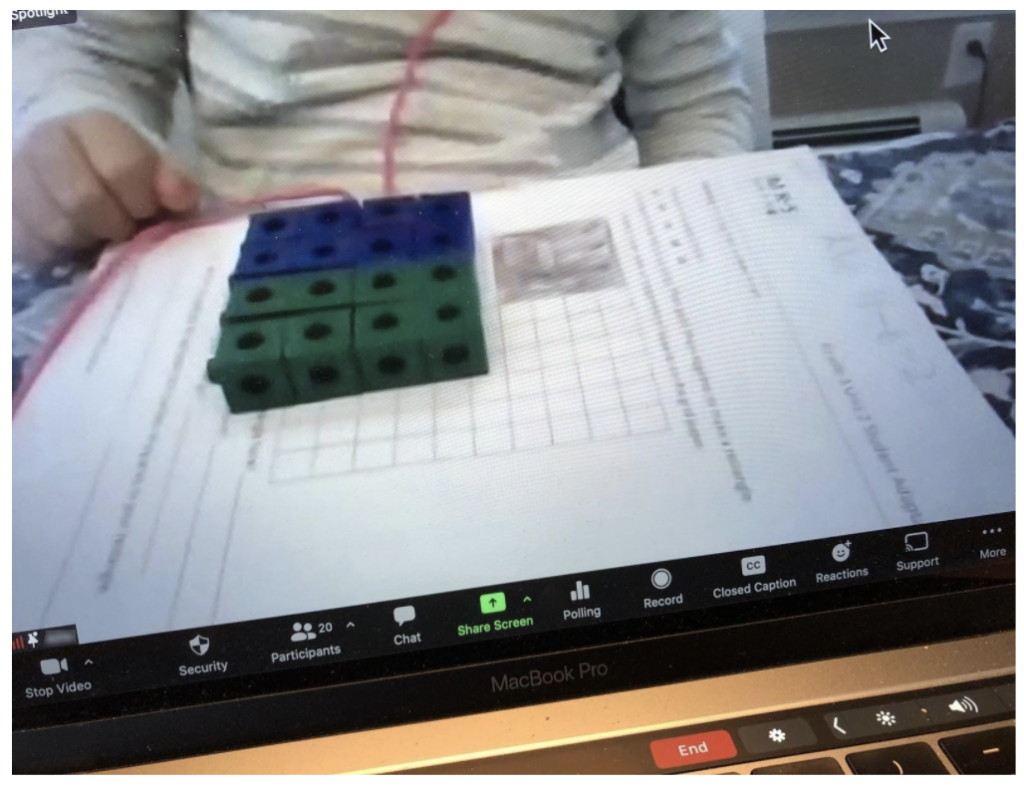

This student tilted their chromebook cover downward to allow all of us to see their work with the cubes. The teacher then used the spotlight tool to allow others to examine the work more closely.

Central Belief #3:

Students listen to, respond to, and value each other’s thinking.

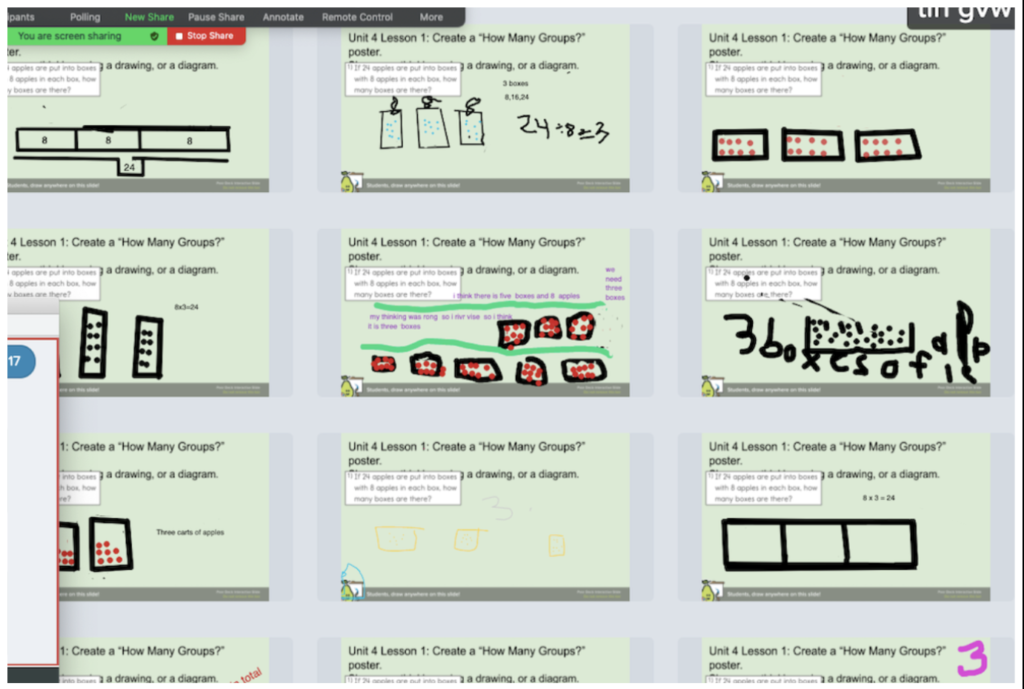

Strategy: Use a tool that allows the teacher to see student work live, and then select and sequence for student presentation and discussion.

Pear Deck Teacher View.

Different online tools allow teachers to view student work in live time. Teachers can then select student work to share with the class. For example, the teacher might select different strategies to compare or contrast, or the teacher might select the work of a student who does not regularly speak up in front of the whole class.

Using Peardeck, teachers can star student work to be shared.

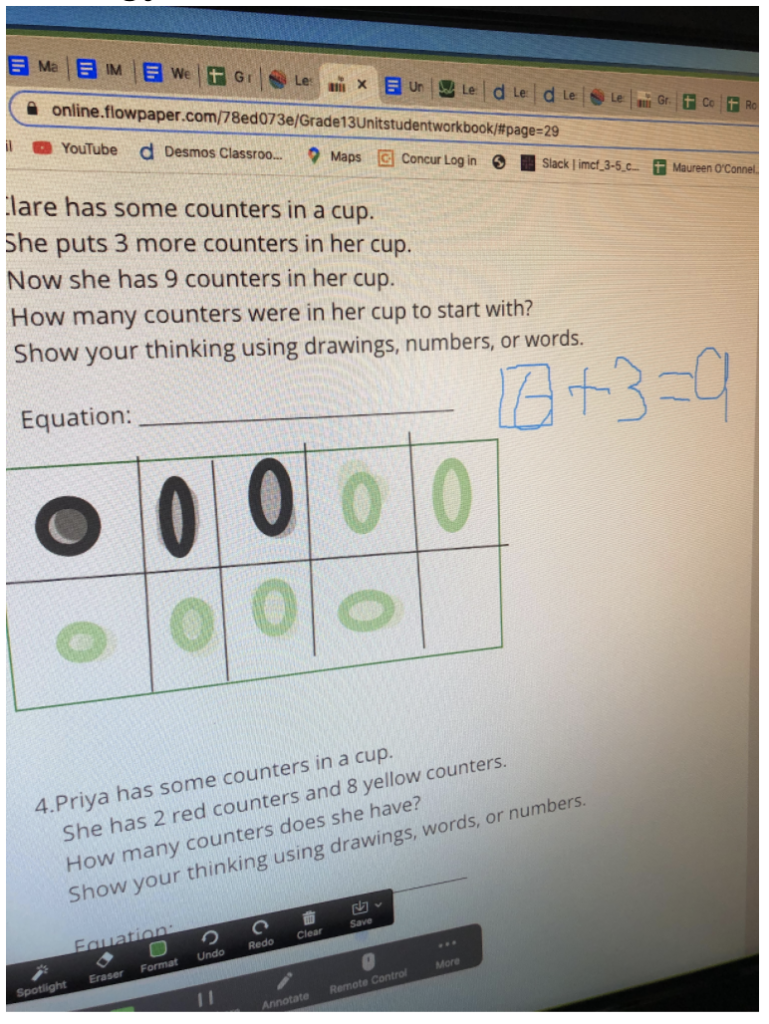

Strategy: Students annotate on the shared screen.

Students are able to annotate on the shared screen, if these settings have been previously activated. This can be a powerful form of communication. Students are able to make their thinking visual for their peers without using the teacher as an intermediary.

Strategy: Use student devices/chromebooks as document cameras to create a “gallery.”

To share their work, students can either hold up what they have written or tilt the screen downward. When many students share simultaneously, the class can engage in a gallery walk of student ideas. The teacher can also select and sequence student work for sharing.

Central Belief #4:

Students learn by collaborating with each other.

Time for working with peers allows for students to co-create understanding. We are better together.

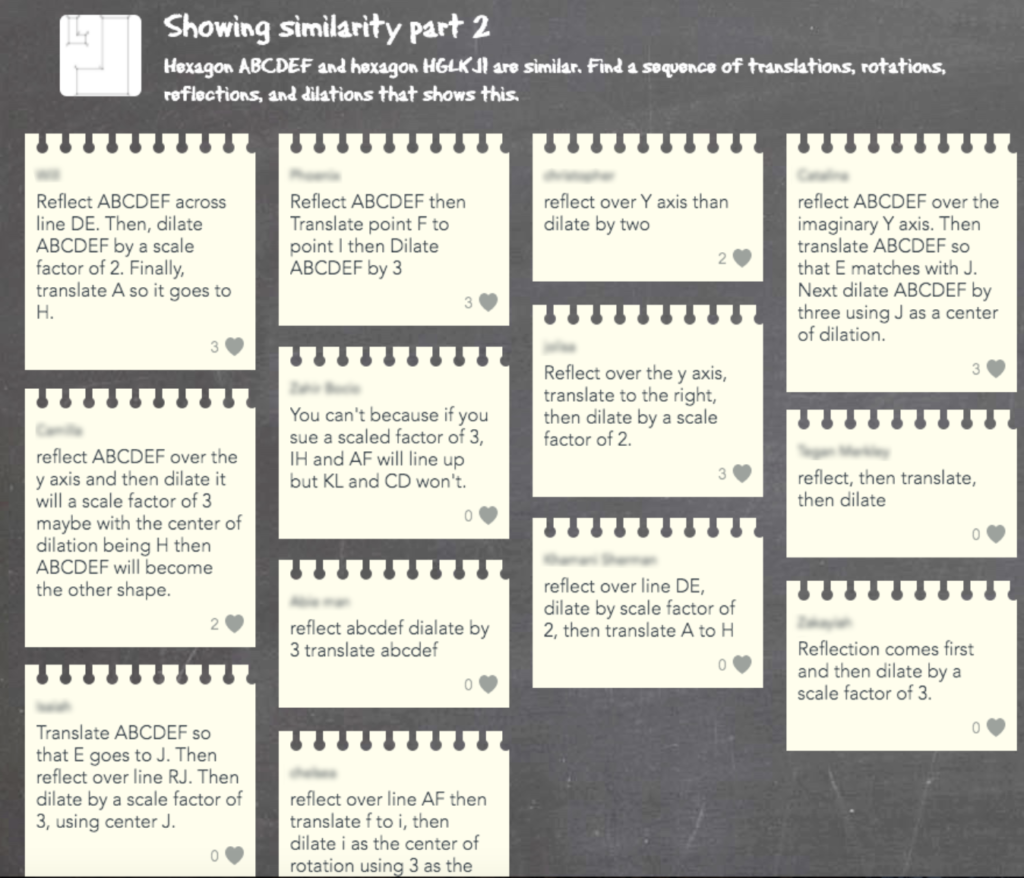

Strategy: Allow students to respond to one another.

Marcelle used resources that allowed students to post and react to each others’ thinking. This kept student work at the center of synchronous and asynchronous learning time.

Using Near Pod, students posted and then reacted to each other’s thinking.

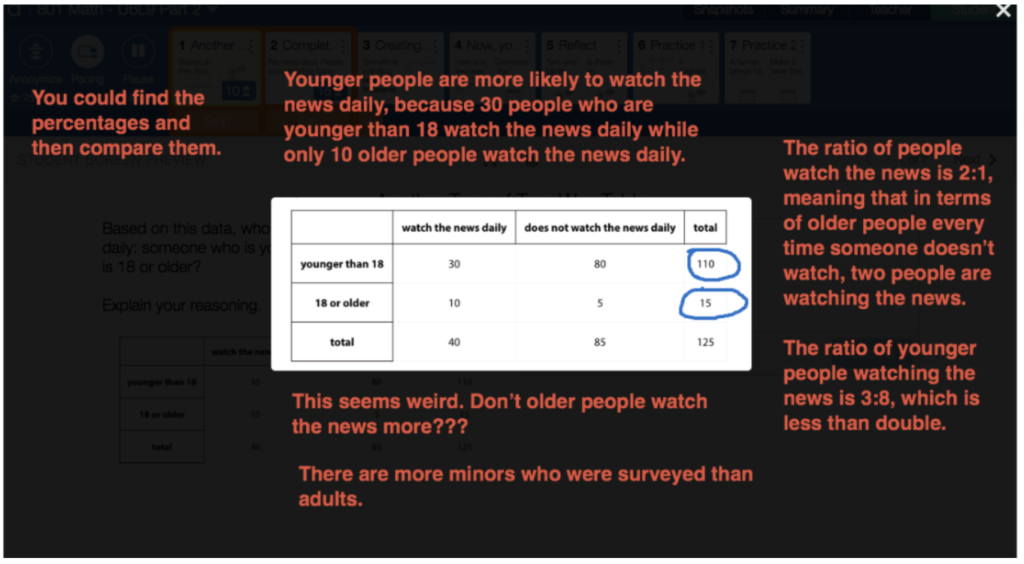

Strategy: Give quiet time for students to collaboratively annotate the screen on Zoom.

Students refined their ideas about this two-way table. Students annotated on the screen using the typing feature, without talking, creating a virtual “chalk talk.”

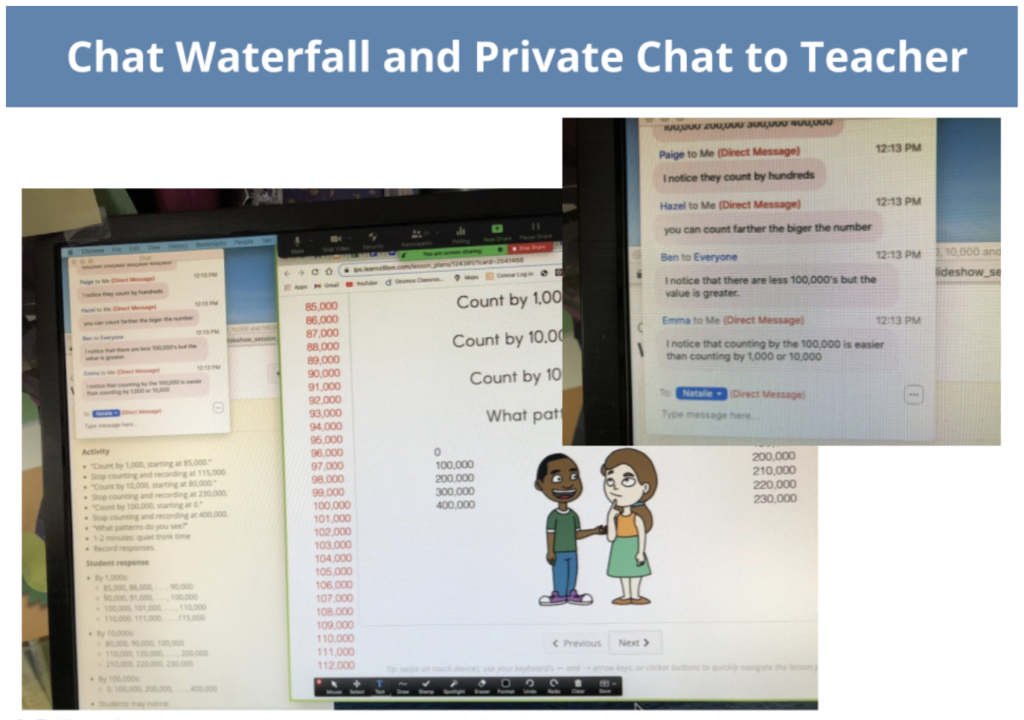

Strategy: Using chat features (direct message and group message) allows students to participate at their comfort level.

All voices and ideas are welcome.

A “chat waterfall” happens when students are asked to record a response in the chat window but refrain from hitting “send.” Then the teacher signals for everyone to send their message, and they all appear at once, forming a “waterfall” of responses. This is a low-stakes way for many students to participate.

Students can also send private messages to a teacher about any number of things, including the math content. It is an even more low-stakes way to share or rehearse thinking without potential judgment from peers.

Learning Math by Doing:

The 5 Practices

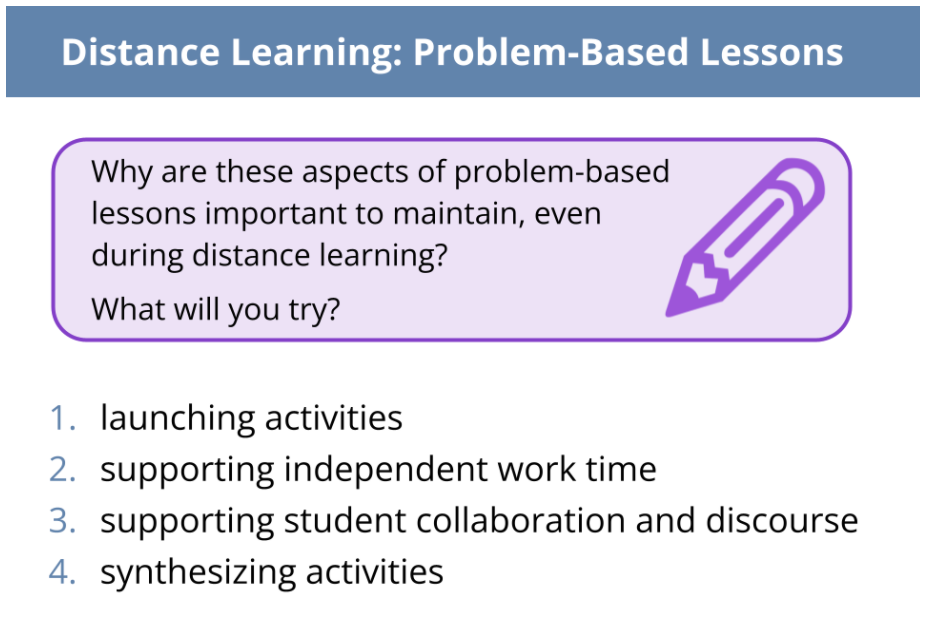

Through our experiences with colleagues and students we also named IM problem-based lesson components that were crucial to maintain in distance learning.

The examples we shared demonstrate how the 5 Practices for Orchestrating Productive Mathematics Discussions (Smith and Stein) thrived in distance learning. Marcelle and I found that seeing all replies at once facilitated selecting and sequencing of work that would be presented by students to advance the lesson learning goals. It afforded both powerful opportunities for connections between diverse representations and strong syntheses.

We learned that, even when feeling pressured for time during live meetings, it was crucial to offer time for connections, completing the IM launch activities, supporting independent work time, supporting student collaboration and discourse, and including synthesizing activities.

In the final section of the webinar we discussed strategies for planning IM units and sections in a distance setting. We identified IM-created resources for distance and unfinished learning, the IM Community Hub, and the IM blogs as resources for all.

IM is designed to elevate student ideas. Elham Kazemi asks, “In the classroom, when children gift us their ideas, what kind of relationship do we establish with them? How do we reciprocate?” As we position for success in teaching IM in distance learning, we stand ready to employ proven moves to celebrate and amplify these gifts and hold them at the center of all we do.

Next Steps

If you are planning for short- or long-term distance learning using IM, please consider watching the full webinar for specific content and technical tips for keeping student thinking at the center of your remote lessons. Please let us know what strategies work for you and your students as you take this journey together apart.