Catherine Castillo, Sr. Specialist, Implementation Enablement

Claire Neely, Sr. Specialist, Implementation Enablement

“Both rigorous performance evaluation and frequent formative feedback are important building blocks for promoting a strong teacher workforce. Mounting research suggests that we are watering down both practices by trying to deliver them within a single system. It’s time we more narrowly focus the goals of evaluation systems and expand investments in formative observation and feedback.”

— Christian & Goldhaber (2022)

Classroom observations are a vital tool for teacher growth—but when evaluation and feedback are intertwined, both can suffer.

Unfortunately, schools often lack the resources to hire dedicated content coaches, and so administrators must assume the role of both instructional leader and evaluator, trying to support teacher growth while simultaneously rating performance.

So how can principals honor both responsibilities without compromising either?

Separate the Roles—and Name Them Clearly

Aguilar (2016) identifies three roles managers play: evaluator, coach, and feedback provider. The key is transparency. By naming the stance they are taking during a conversation, principals help teachers understand what kind of interaction to expect and how to engage.

A simple statement like, “I’m stepping out of my evaluator role and into my feedback-provider role,” can completely shift the tone and trust level in a post-observation conversation.

Why does this matter? Evaluation and feedback serve fundamentally different purposes. Evaluation is about rating the effectiveness of teachers. This is often at odds with the messy work of feedback and coaching, which involves learning through iteration, reflection, and practice.

Adult learning theory reinforces this distinction. Adults learn best when they:

- Understand why they are learning something

- Can be self-directed

- Learn through experience

- Have a problem or goal that motivates them

- Feel respected and involved in the process

Knight (2021) echoes this:

“Most of us get a great deal of pleasure out of telling others how to solve their problems. But effective coaches know they need to refrain from fixing people and focus on creating conditions where people unlock their own potential. This means that coaches should only share their expertise when it is clearly needed.”

In order to understand how to best provide feedback to teachers, we can look at both adult learning theory and studies that uncover the types of feedback teachers find valuable. Recent studies show that teachers value feedback that is:

- Quick and actionable

- From trusted colleagues and students

- Focused on student learning

- Delivered in meaningful, non-threatening ways (ASCD, 2022)

Notice the connection: Feedback works best when adults are treated as learners, not subjects of judgment.

Shifting Classroom Observations: Questions Leaders Can Ask

In light of these findings, leaders might find it helpful to think about these questions when observing classrooms.

1. What professional learning goal has this teacher identified for themselves?

Using a tool such as the IMplementation Reflection Tool, teachers have an opportunity to select a specific practice they would like to refine, gather evidence of their shift in practice, and identify next steps to try out. Knowing the goal teachers have selected for themselves is paramount in feedback conversations if we want to support teachers in driving their own learning.

2. What are the learning goals of this lesson and activities?

Feedback is most effective when it is rooted in the mathematics. Having an understanding of the mathematics students will be engaged in during the observation as well as the learning goals the teacher is building toward keeps post-observation conversations grounded in student learning, not surface-level impressions.

3. What am I seeing and hearing during this lesson?

Problem-based learning can look and sound very different from traditional instruction. A problem-based classroom is rarely a quiet classroom where students are neatly sitting in rows and consuming information. Rather, it is active, messy, and full of conversation. Students work individually and in groups and move around as they problem solve and talk about mathematics.

IM’s Model for Problem-Based Instruction

4. How can I help teachers uncover their own learning opportunities?

Observing through a problem-based learning lens and collecting objective data—like student comments, teacher prompts, and participation patterns—provides a powerful foundation for reflective, teacher-led conversations. When feedback is rooted in data rather than judgment, teachers are more likely to reflect honestly and identify their own learning opportunities. This approach positions observers as partners rather than critics.

5. What if teachers need more explicit guidance?

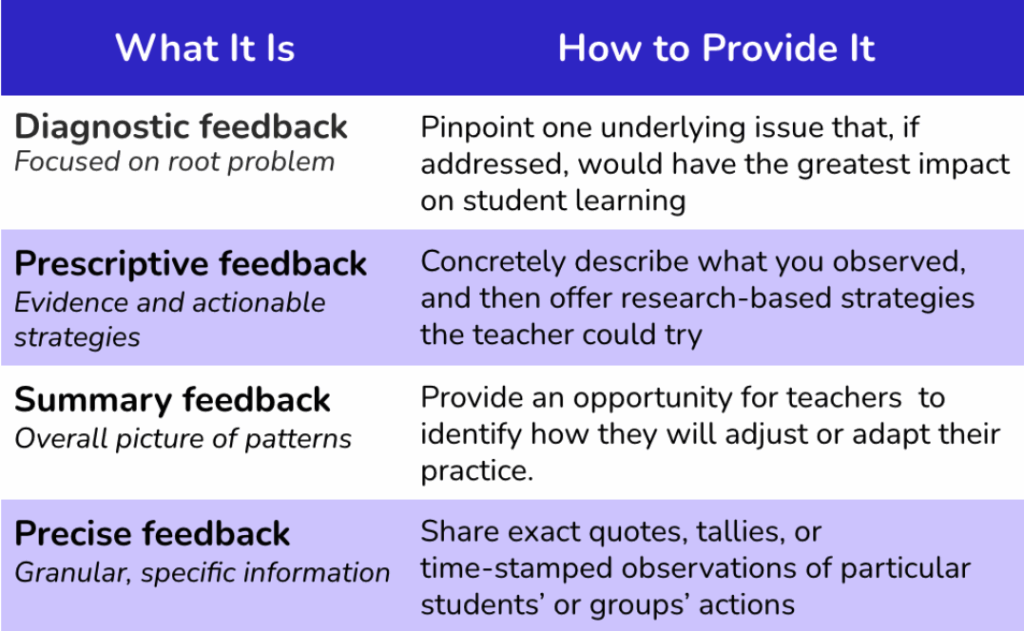

Sometimes, teachers feel stuck or unsure what to try next—we’ve all been there. Jackson (2013) identifies four types of feedback that support teacher growth as they move from novice to expert: diagnostic, prescriptive, summary, and precise feedback.

Modified from Jackson, R. R. (2013). Never underestimate your teachers: Instructional leadership for excellence in every classroom. Corwin.

The Power of Regular, Non-Evaluative Observation

When classroom observations are a regular part of learning and aren’t simply focused on evaluation, teachers feel empowered to try hard things. Peer feedback in the form of learning walks can both build a positive school culture and transform instruction.By positioning teachers as experts in their craft, and providing time and space to learn from each other, we value the unique talents our teachers bring and support them in setting and achieving their own goals.

Conclusion

Classroom observations don’t need to be a source of anxiety. By separating evaluation from feedback and clearly naming your role in each conversation, you create space for honest reflection, experimentation, and growth.

Feedback aligned with teacher-selected goals and student learning becomes a powerful tool for professional growth rather than a measure of judgment. Observations can then serve as opportunities to unlock teacher expertise, build trust, and strengthen instructional practice across your school.

Aguilar, E. (2016). The art of coaching teams: Building resilient communities that transform schools. Jossey-Bass.

ASCD. (2022). What teachers really want when it comes to feedback. Educational Leadership, 79(7). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/what-teachers-really-want-when-it-comes-to-feedback

Christian, A., & Goldhaber, D. (2022). Better teacher feedback can happen outside of the evaluation process. Brookings. www.brookings.edu/articles/better-teacher-feedback-can-happen-outside-of-the-evaluation-process/

Knight, J. (2021, December 6). Should coaches be experts? The Learning Zone. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-learning-zone-should-coaches-be-experts?

Next Steps:

Small, intentional steps—like clarifying your stance, centering teacher goals, and capturing actionable data—can transform your observation cycles into meaningful moments of learning. Try one of these strategies in your next observation and notice how it shifts the conversation.

Interested in learning more about aligning classroom feedback with problem-based instruction? Check out Key Action 6 in the Quick Start Guide for Implementation, IM’s roadmap for launching IM Certified® Math in collaboration with teachers.

Catherine Castillo

Catherine Castillo

Sr. Implementation Specialist

Catherine Castillo (she/her) has spent her career supporting students and educators as a teacher, instructional math coach, math recovery intervention specialist, and district math coordinator. Catherine now serves as a senior specialist on the Implementation Portfolio team where she creates resources that support coaches and instructional leaders with IM implementation. Catherine is passionate about cultivating positive math identities in students and teachers and supporting the implementation of problem-based teaching and learning.

Claire Neely

Sr. Implementation Specialist

Claire Neely (she/her) received an MS in educational studies with a specialization in mathematics from Johns Hopkins University. Claire has spent her career in education teaching and coaching mathematics in schools of all kinds: Title I, charter, language immersion, traditional public, Montessori, K–8, middle, and high schools. After transitioning out of schools and into professional learning, Claire now serves as a senior specialist on the Implementation Portfolio team creating resources that support math coaches, curriculum specialists, and administrators with IM implementation.